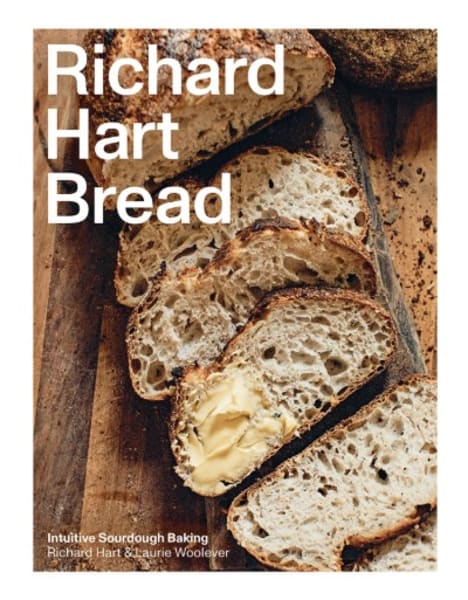

“For years, I’d been making a bread called country loaf, which is a fairly common name for a slightly wheaty sourdough bread,” says Richard Hart. “I started calling my bread city loaf when I moved to Copenhagen, seeing as I was in a city. You can call your bread anything you like. It’s as simple as that. When you make something that’s popular, whatever you call it sticks.”

City loaf master recipe

Makes two 950g loaves

Start off with all your equipment at hand, and keep a bowl of warm water nearby to easily rinse off your hands and dough scraper.

Starter

Dough

Additional ingredients

A handful each of all-purpose and rice flour (for coating baskets and tops of loaves).

*As of this writing, I am baking in Copenhagen, and the specifics of this recipe reflect those climatic conditions. The temperatures listed here are for bakers working in temperate climates. If you’re in a very hot place, the water should be cooler (30°C), to avoid speeding up fermentation too much. Otherwise, the temperature of the hot water (40°C) is perfect because once you’ve added all your other ingredients, the temperature of the dough will be around where you want it, 30°C.

Timing

Day 1 (morning): Feed starter, autolyse and mix dough, ferment, preshape, and final shape: a total of 8 hours (most of which is allowing the dough to bulk ferment and proof), plus an overnight cold retard of up to 12 hours.

Day 2 (morning): Preheat oven, transfer dough to Dutch oven, score, and bake: a total of 2½ to 3 hours.

Equipment

Medium and large mixing bowls, digital thermometer, flexible plastic dough scraper, bowl or pitcher of warm water (for rinsing), two tea towels, bench scraper, two bannetons (proofing baskets), cast-iron or enameled Dutch oven (with a flat, handleless lid), lame or scissors, cooling rack.

Day 1

Feed the starter: In a medium bowl, use your hands to mix the water, flour, and 12-hour starter for a minute or so. You’ll notice that you’re making 250g freshly fed starter, but the dough calls for only 200g. The extra 50g are held back as starter for tomorrow’s bread.

Take the starter’s temperature. At this point, it should be about 30°–35°C. Don’t worry if it isn’t in this range; simply place the bowl into a larger bowl of warm or cold water, if necessary, depending on which direction you need it to go.

Make sure your dough scraper and a bowl of warm water are close at hand.

Scrape the excess mixture off your fingers back into the bowl, then rinse your hands in the bowl of warm water. Now, use your plastic scraper to push the starter mix together, getting everything off the insides of the bowl and into one cohesive body. Cover the bowl with a tea towel and leave the freshly fed starter in a warm, draft-free place.

Set a timer for 45 minutes.

Autolyse the dough: In a large bowl, combine both flours and 650g of the hot water (you’ll add the remaining 100g water in the next step), and use your hands to mix them until there is no dry flour remaining. That’s all. You don’t need to beat the dough; just mix it together. Use the plastic scraper to scrape the dough from your hands back into the bowl, and rinse your hands in the bowl of warm water, along with your scraper. Use the damp scraper to scrape down the insides of the bowl, making sure all the dough is together and your bowl looks clean. Then, cover the bowl with a tea towel.

This dough mixture will need to rest for at least 20 minutes, and up to 45 minutes, before you combine it with the freshly fed starter. This stage of the process is called autolyse.

Mix the dough: After the timer for the starter has gone off and you’ve given the dough at least 20 minutes to autolyse after mixing, scrape 200g of the freshly fed starter into the bowl with the resting dough. Reserve the remaining 50g starter for the next day’s bread.

While holding the bowl still with one hand, use your other hand to gently massage the starter into the dough. Now add 50g of the remaining water, which will make the dough slippery and easier to mix. Keep massaging. Once the water is fully absorbed, the mixture will stop being slippery and will have a sticky consistency.

Add the salt and remaining 50g hot water and continue to mix until the water has been absorbed and the salt is dissolved into the dough. The dough should feel soft and pull and stretch easily.

Take the dough’s temperature. In a cold climate, it should be around 31°C. In a hot climate, it should be around 27°C. You want to aim to keep it at that temperature throughout its whole bulk fermentation (which starts in the next step). If it’s too cold, set the bowl in a larger bowl of hot water to warm it up. If it’s too warm, do the same, using cool or ice water. You don’t need to be hypervigilant—it’s not an exact science—but check it every 45 minutes to 1 hour during bulk fermentation and adjust accordingly.

Bulk ferment the dough: Wash your hands, scrape down the insides of the bowl, and cover the dough with a tea towel. Set a timer for 45 minutes.

This is the beginning of bulk fermentation, which will take about 4 hours total, including a few folds. Letting the dough rest for 45 minutes before you fold will make it much stronger. The gluten bonds, which started to form the second you added water to the flour, will continue to develop as the dough rests.

The first fold: Once the timer goes off, it’s time to fold the dough. Keeping the dough in the bowl, gently pull it toward you and fold it over itself. At first, it will pull very easily and stay where you leave it. Rotate the bowl a quarter turn and repeat the fold. Repeat this process, giving the bowl a quarter turn each time. After four or five folds, the dough will be as tight as it needs to be, and the dough will resist being folded any more. That’s when you know it’s time to stop.

You do this folding for two reasons: to help the gluten do its thing and to stay connected to your dough. How’s it going? Check its temperature and, again, adjust accordingly with a bowl of warm or cool water if necessary, to bring it into that 30°–35°C range. Cover it back up with the towel and set a timer once again for 45 minutes, for the second rest.

The second fold: Once the timer goes off, repeat the gentle folds as before and read your dough again. You should see evidence of a few air bubbles below the surface. If you don’t, don’t worry. It’s only just the beginning of the fermentation.

Check the dough’s temperature and adjust accordingly. You’re about to leave the dough alone for 2½ hours, so it’s important to make sure that it’s nice and comfortable while it rests, so that it will properly ferment. Remember, we’re going for maximum yeast activity, which happens in that ideal temperature range.

Continue bulk fermentation: Now set the timer for 2½ hours.

Do your thing while the dough does its thing, which is to say, the final stretch of bulk fermentation. After this long rest, you should start to see more and larger bubbles under the surface, more of the bounciness as described above, and less moisture on the surface.

Divide and preshape: By now, the dough has had 4 hours of bulk fermentation, and if it has been kept at a nice consistent temperature and the room is comfortably warm, it will be well fermented. If you discern that it’s not quite there yet—not too bouncy, no visible bubbling, kind of slack—give it another 30 to 60 minutes.

You might be used to flouring the work surface before putting your dough onto it, but trust me, you don’t need to for this style of bread. You actually want the bottom of the dough to stick to the surface, which will help create tension.

Gently use your plastic scraper to ease the bread out of the bowl and onto your work surface. Treat it tenderly. You don’t want to de-gas it.

Wet your hands to keep them from sticking to the top of the dough. Use your bench scraper to quickly and firmly divide the dough in two. Get one piece directly in front of you. Don’t be afraid to pick it up with your bench scraper and move it to where you need it. Using your hand and bench scraper in unison, work the dough toward you, using your fingers to swiftly tuck the outer edges of the ball under the surface of the loaf, shaping it into a neat round with good surface tension. Confident, swift movements are best. There will be some sticking, which is why wet hands are essential. Try not to work the dough too much. You don’t want to let out the beautiful gases you’ve spent all this time creating. It takes a lot of practice, but you’ll know when you have it right—it will come together and have a nice tight surface. Repeat with the other piece of dough.

Another rest: Leave your two preshaped loaves to rest, uncovered, on the work surface for 45 minutes to 1 hour. After this rest they will have lost some of that tension that came from the preshaping and will look more relaxed than when you left them.

Final shape: Sprinkle a combination of all-purpose and rice flour into the bannetons and sprinkle a very light dusting of all-purpose flour over the tops of the loaves. Using your bench scraper, shimmy the dough into an oval shape, using just a few moves to get it into more of an oval than a round. Hold one hand over the centre of the loaf, take your scraper in the other hand, and scrape evenly across the surface of the table toward the loaf, lifting it up and into the other hand. Put down the scraper and cradle the loaf in both hands. Now fold it inward and gently place it into the basket. If it tries to fall back open, you can gently pinch it together at the top. That’s it. It’s safe and happy just the way it is.

No need for aggressive shaping.

Cold retard: Lightly flour the loaves again, using a combination of all-purpose and rice flour, to keep the towel from sticking, then cover the baskets loosely with a towel, and let the loaves sit overnight, or up to 12 hours (at most 15 hours), to develop flavour. The ideal temperature is 12°–15°C, so if you have a cool cellar or a wine fridge, place them in there. Or if it’s that temperature range outside your windowsill and you don’t have a rat, bear, or raccoon problem, place them outside, covered with a tea towel. Otherwise, leave them on the counter in your kitchen for 2 hours, then transfer to the refrigerator.

DAY 2

Preheat the oven and Dutch oven: The following day, preheat the oven to 260°C for at least 1 hour, with your Dutch oven inside to get radiant fucking hot. This vessel will be an oven inside the oven.

Once the Dutch oven is preheated, take it out, but be careful: it’s radiant fucking hot. Use heavy-duty oven mitts or a few layers of dry tea towels when handling it. Place it on a sturdy, heatproof surface. Take the lid off and lay it down carefully, upside down. These vessels are designed to hold their heat, so don’t panic or rush; you have time.

Take one basket of chilled dough out of the fridge. Gently loosen the edges of the loaf with your fingertips and flip the dough straight onto the screaming-hot lid.

Score the loaf: Cut scores into the top of the loaf, using either your lame or scissors. Carefully invert the Dutch oven pot over the dough, to cover it like a dome.

Bake the loaf: Set the inverted Dutch oven back inside your oven, reduce the temperature to 230°C, and set a timer for 20 minutes. As your bread bakes, water will escape from the dough. Baking the bread in the closed environment of your Dutch oven ensures that those water vapors are trapped, steaming the bread in the process and allowing the loaf to rise fully.

After 20 minutes, that steam will have done its job. Remove the inverted pot, so the loaf is directly exposed to the oven’s heat. Set the timer for 20 more minutes and let the loaf finish baking. Since you’ll be baking a second loaf, leave the inverted pot in the oven so it stays hot for the next round.

I prefer to bake my bread pretty dark; I love the taste of a nice caramelized crust, but you’re in charge here, so you decide when to pull it out.

If you can wait, you should let the loaf cool on a cooling rack before cutting it open. The inside structure of a bread that’s screaming hot from the oven will be gummy and not properly set. Give it at least an hour.

Once you have pulled the first loaf from the oven, repeat these steps with the second loaf, transferring it from basket to pan lid, scoring it, covering it with the inverted pot, and baking for 20 minutes covered and 20 minutes uncovered.

Richard Hart Bread (Hardie Grant, $55) is available from good booksellers and online now; follow his adventures at @richardhartbaker, @hartbageri and @greenrhino_mx.